The oceans cover c.70% of the Earth’s surface, yet the vast majority of our seas and oceans remain inaccessible to permanent structures, with most marine use occurring within 12 nautical miles of the coast. 38% of UK waters are designated marine protected areas, so there’s evidently a need to optimise the area of the UK seas subject to marine development. Co-location of different types of development is an option that could help, and co-siting aquaculture (especially seaweed farming) within offshore wind farms has garnered particular interest, most recently with Amazon announcing funding for research into co-location in the North Sea.

What is the opportunity for the co-location of offshore wind and seaweed?

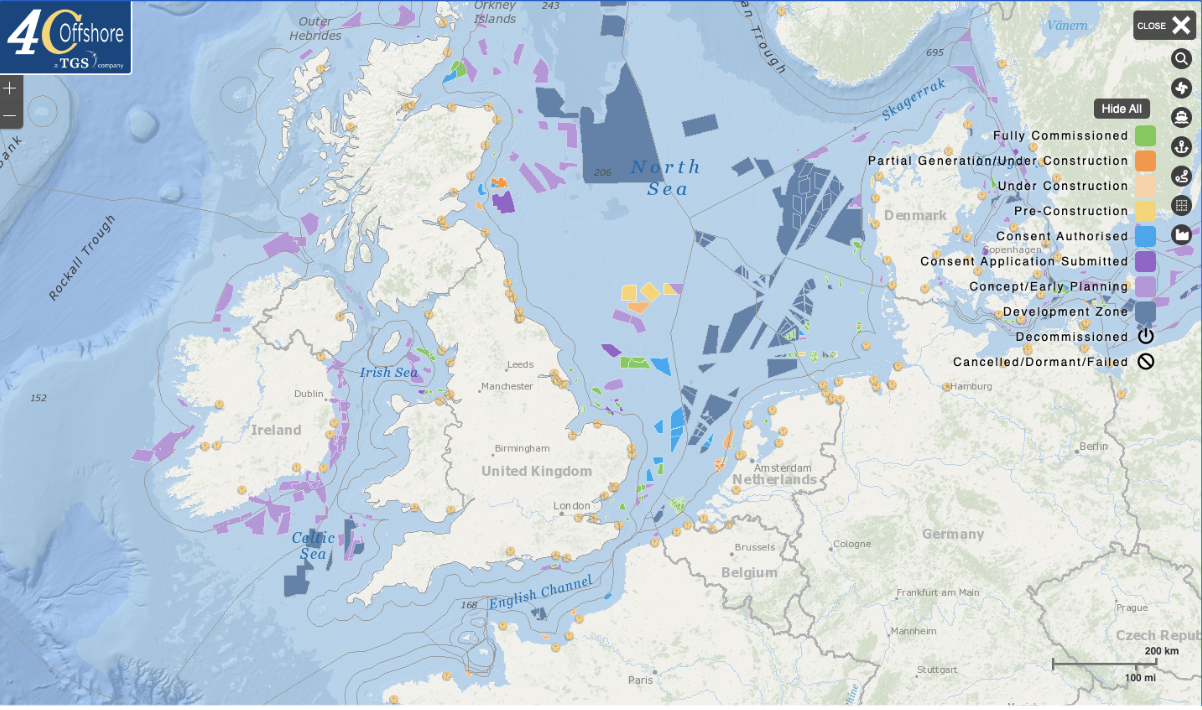

As of December 2021 there were 42 operational wind farms in UK waters with 8 more under construction1. The UK government has set an ambitious target of increasing offshore wind fivefold to 50GW by 2030, demonstrating the long term and continued commitment to the rapid development of the sector in UK waters. The increasing adoption of floating foundations is enabling offshore wind to move into the deeper waters of the UK, opening up further areas of ocean. One potential advantage of floating offshore wind (FOW) farms is the reduced sea bed installation requirements for mooring anchors and chains, compared to fixing foundation structures directly to the sea bed. Currently there are three European floating offshore wind farms, two in Scotland and one in Portugal2 with a significant global development pipeline in progress, including off the coasts of UK, France, Norway, South Korea and Japan.

With this development pipeline, there’s potential to enhance sites and optimise the use of the UKs marine environment through the co-location of aquaculture - particularly seaweed.

Seaweed is well documented for its efficiencies in carbon dioxide absorption, and has multiple use-cases including; fuel, fertiliser, animal feed, human consumption, and cosmetics. There’s also a growing demand for seaweed derived biochemicals for nutraceutical and biotech - such as eco-friendly packaging (e.g. Oceanium and EarthShot Prize winners Notpla). However, existing seaweed growing practices are small and bespoke making them expensive. Production scale needs to increase if commercial demands are to be met.

South West Mull and Iona Development Trust seaweed farm on the Isle of Mull, Scotland. As of 2022 the largest operational farm in the UK with 6 km of line deployed. (Courtesy of Leigh Eisler and South West Mull and Iona Development Trust.)

The current location of seaweed farms are limited in expansion scale, due in part, to the risk of infringing on other users of the marine environment. Co-locating within other offshore developments, such as offshore wind farms, would help mitigate this, and provide access to large scale dedicated growing areas which are currently lacking.

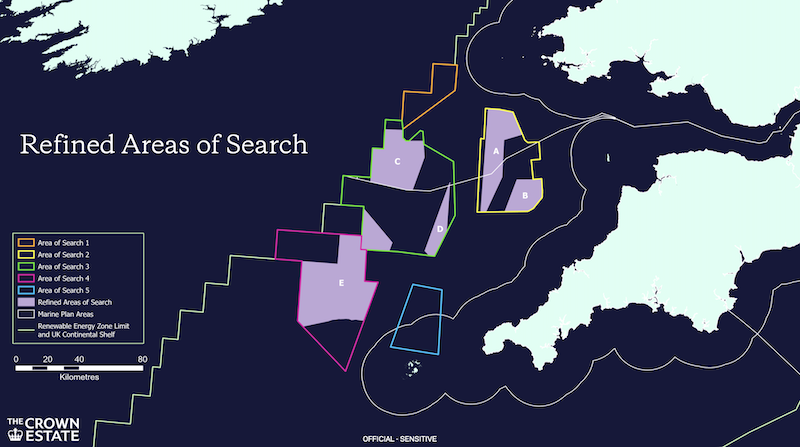

In the Celtic Sea, The Crown Estate are now planning to lease sites for floating offshore wind development with a capacity of 24 GW. Broadly this could equate to a potential area of development of up to 4,800 km^2 (based on a 5 MW/km^2 density). If seaweed production were to be co-located, then even with conservative assumptions, this could afford the growth of around 24 million tonnes of seaweed, almost double the current seaweed market size3. At current market prices of approximately £1 a kg, that could be a £24 billion market acoss use cases such as cosmetics, food and fertiliser.

Farmed kelp on the line

It’s clear that co-locating seaweed farming and floating offshore wind farms would enable a more efficient use of the marine environment, but are there other benefits to co-location?

There are lots of reasons to consider co-location, not least the significant set-up cost savings. For instance the ability to establish seaweed farm moorings at the same time as installing moorings for the wind farm. It also enables economies of scale, meaning the potential for much larger seaweed farms that can grow more in a single area.

Biodiversity is another key area. With the Environment Act 2021 the UK government is increasingly focusing on the idea of marine net gain for all development projects. This will mean that marine biodiversity must be improved by any marine development activity, such as offshore wind farm development and / or aquaculture installations. To achieve this, marine activity has to not only mitigate its potential impacts on the environment, but also work to create habitat enhancement to offset those impacts– for example, by encouraging and supporting marine biodiversity.

Seaweeds form the basis of many essential marine habitats. Biodiversity in kelp and other seaweed forests around the world is often extremely high, providing refuge and nursery grounds for ecologically and commercially important fish species. Studies4 have shown that seaweed aquaculture can also improve the benthic quality index (BQI) of an area contributing to species abundance.

Floating offshore wind farm infrastructure also offers a unique opportunity for supporting marine biodiversity. The design of floating platforms and the requirement for moorings, is expected to reduce pre-existing commercial fishing efforts (such as trawling or dredge fishing activities). This has the potential to not only lead to biodiversity net gains, but in the longer term result in positive gains for commercial fisheries as the increased diversity and productivity spills out into adjacent areas5.

A co-located seaweed farm within floating offshore wind farms could help create and extend any preferred exclusion zone, further stimulating the habitats required to reach marine net gain goals. Ørsted and SeaGrown have recently announced a partnership to develop biodiversity monitoring on offshore seaweed farms, with the aim of incorporating them within floating offshore wind farm sites. This is a huge step forward and indicates the importance of future co-use.

Increasing marine biodiversity also offers a unique income stream opportunity. At COP15 in Montreal, biodiversity credit schemes were discussed as a way for monetising and supporting schemes that would increase biodiversity. Blue Carbon Credit schemes offer potential revenue streams for both Floating Offshore Windfarms and seaweed farms as demonstrated by the first Blue Carbon credits awarded to an urchin farmer in Japan for kelp bed restoration.

So, if there is opportunity in co-siting floating offshore wind farms and seaweed farms - why isn’t it already happening? What’s preventing co-location?

Licensing is arguably the most significant barrier. In Europe and around the UK, seaweed farms are currently situated in near-shore locations, in shallow water (<50 m deep). In these areas the marine environment is subject to many competing uses and priorities which makes identifying appropriate sites and obtaining the necessary consents challenging for small scale schemes.

Commercial challenges: Current seaweed farming methods are expensive and labour intensive. It’s argued that co-siting within an offshore wind farm could increase costs due to increased travel, fuel and logistical challenges (weather, rough seas, deeper waters)associated with offshore activities. In fact, the increased scale of farm sites will actually enable industrialised cost benefits which will offset these challenges.

Where is there precedence?

As we look beyond our own shores we can already see marine co-use in progress.

The extent of current offshore wind activity around the UK coast/North Sea. (Courtesy 4C Offshore)

Wier and Wind is a pilot project in the North Sea, which sees a collaboration between an offshore wind farm operator, seaweed companies, and research institutes in Flanders and the Netherlands. Wier and Wind have deployed a test seaweed farm located within a wind farm boundary, 12km off the coast.

Despite being a leader in the establishment of offshore wind, the UK risks being left behind in the wider benefits of marine use unless we see some movement soon to consider the co-location benefits of offshore development.

So what is Seaweed Generation doing to enable change to make this happen?

Seaweed Generation are developing an approach that focuses on automation in seeding, monitoring, and harvesting to combat key challenges in cultivation methods. Current labour intensive long-line practices are ill suited to offshore conditions, and we recognise that automation will be key if we’re to find a scalable and cost effective offshore solution.

Seaweed Generation are developing systems that have the ability to respond to bad weather and rough sea states, making it a perfect partner for floating offshore wind co-location. We are also creating tools and adapting known methodologies to remotely monitor marine biodiversity around seaweed farms. The longer term aim is to provide remote (and cheaper) biodiversity monitoring to floating offshore wind farms, by reducing the requirement of marine biodiversity survey vessel time. These systems are under development, with clear potential to collaborate with the nascent floating offshore sector (following the path Ørsted have already taken).

Appropriate support and funding for these types of projects will be key if the UK is to keep pace with the rate of progress we see in other territories. For example, North Sea Farmers offshore test site (OTS) is located 12 km off the coast of Scheveningen. The site is a space created for start-ups and scale-ups to test innovations in challenging offshore conditions. We urgently need the regulatory, policy and licensing frameworks in the UK to follow this lead and ensure future facing marine development doesn’t stumble at the first hurdle.

Arguably, it’s now really about incorporating co-use within marine developments projects from the outset - and there’s lots to choose from. The recent Scotwind offshore wind leases included multi Gigawatt floating offshore wind projects, and this is being followed by The Crown Estate’s Celtic Seas leasing round which is planned to award initial 4 * 1 GW leases for floating offshore wind later this year6, with a further 20 GW to follow.

Courtesy: The Crown Estate, Celtic Sea - Floating Wind, October 2022 update.

There’s clear scope to look at opportunities for co-locating seaweed farms within these sites, where co-location ultimately provides a cost-effective, space efficient, net positive use of our oceans.